We know this much: Based on his last term in office, Donald Trump isn’t a big fan of science, regulation, or international alliances. So, how can we still save our planet given this new political reality? Will communication play an even more important role in this effort as we work to keep the US involved? Or will the market incentives in our policy proposals need to be more heavily tilted in favor of industry? Or will we need to rely primarily on state and city governments to get started?

And what will happen to DOE investments in clean energy research and carbon capture—by far the largest investments in the world—and the work of critical agencies like NOAA?

A couple of clues coming in. From the New York Times (What a 2nd Trump Presidency Means for Climate Change – The New York Times): “States are now likely to become a bulwark against federal efforts to undo climate policy. ‘The locus of climate action is going to shift to the states,’ said Martin Lockman, a fellow at the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University. ‘Unless there is a complete reversal of the Inflation Reduction Act, this is something where climate issues, even in red states where they won’t say the word ‘climate,’ the impact on the ground is undeniable.'”

And, “Laurence Tubiana, France’s former climate ambassador and one of the architects of the Paris agreement, insisted that the Paris accord ‘is stronger than any single country’s policies.’ She said that in the nine years since the agreement was signed, many nations have heavily invested in solar, wind, nuclear and other non-carbon forms of energy. There is economic momentum behind renewable power, she said, and by spurning it, the United States would risk forfeiting the future.”

Carbon industry newspaper Carbon Brief offers this analysis: ” A victory for Donald Trump in November’s presidential election could lead to an additional 4bn tonnes of US emissions by 2030 compared with Joe Biden’s plans…. This extra 4bn tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) by 2030 would cause global climate damages worth more than $900bn, based on the latest US government valuations. For context, 4GtCO2e is equivalent to the combined annual emissions of the EU and Japan, or the combined annual total of the world’s 140 lowest-emitting countries. Put another way, the extra 4GtCO2e from a second Trump term would negate – twice over – all of the savings from deploying wind, solar and other clean technologies around the world over the past five years. If Trump secures a second term, the US would also very likely miss its global climate pledge by a wide margin, with emissions only falling to 28% below 2005 levels by 2030. The US’s current target under the Paris Agreement is to achieve a 50-52% reduction by 2030.”

Carbon Brief’s notes that its analysis “is based on an aggregation of modelling by various US research groups. It highlights the significant impact of the Biden administration’s climate policies. This includes the Inflation Reduction Act – which Trump has pledged to reverse – along with several other policies.”

Will the US leave the Paris Accord?

President Trump did this before, withdrawing in late 2020 (one year after giving notice in 2019). However, the US immediately rejoined in 2021 when President Biden took office. Now, if the US gives notice in early 2025, it could withdraw in January 2026, and stay out for many years (since there’s certainly no guarantee the Democrats will win back the White House in 2028). Many of Trump’s corporate and political allies are advising him not to leave Paris. If this happens, though, the US will miss its emission targets. As a result, US carbon emissions could rise 4 billion tons by 2030 compared with the current trajectory.

How will the EU and China react?

Will pulling out of the Paris Agreement create an excuse for the EU to slow down on its climate work? Probably not, but with the EU struggling economically, there might be some political blowback, especially from conservatives, to sticking with stringent green goals if the US ignores these targets and in fact goes in the opposite direction.

How about China? China’s emissions may soon peak since it’s been embarking on an ambitious rollout of clean energy systems, but once the US backs out and tariffs go in place, will they continue down this path? Here again, the future of energy is clean, not fossil fuels, so it’s unlikely this shift will do anything other than create an opening for China to create stronger climate alliances and grab a larger share of the future energy market.

Note also that when Trump withdrew from Paris last time, no other countries followed suit,

Will the US leave the UNFCCC?

Politico and Bloomberg are reporting that lobbyists have already drafted executive orders to get the US out of both the Paris Agreement and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). However, it is unclear whether the US can withdraw from this treaty without approval from two-thirds of the Senate (which won’t happen since Republicans hold only 53 seats out of 100). If Trump tries to force this issue, the matter will be litigated for several years, so nothing is imminent.

If he does succeed, however, then rejoining the UNFCC will also require tw0-thirds approval. So if withdrawal happens, the US will not re-enter in our current political climate. Note that if the US is not a signatory to the UNFCCC, then it can only participate in COP meetings as an observer, which is to say that the world’s richest country and second-largest emitter of CO2 will have no say in policy discussions about the future of our climate.

The Trump Administration will also be able to cut funding for the UNFCCC without leaving the organization entirely.

US-UN gamesmanship isn’t new

The UN budget is funded by a combination of assessed contributions from member states, based on the size of member state economies, plus voluntary contributions for specific programs and agencies. The US has historically been the UN’s largest source of funding, accounting for about 22% of UN revenues ($18 billion) in 2022, so when the US backs out, the repercussions are severe. In the past, the US has left the Paris Agreement from 2020-21, left UNESCO (1984-2003 and again from 2019-2023), left the UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC) in 2018 and rejoined in 2021, announced its intention to withdraw from the WHO in July 2020 (but this move was rescinded by President Biden in 2021), suspended all voluntary funding for the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) in 2017, and reduced voluntary funding for the UN Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the WHO in 2018 by about 30 percent and 20 percent, respectively.

US agencies will turn away from climate policy

President-elect Trump’s choice to lead the Department of Energy, Chris Wright, has experience in energy, unlike his previous DOE nominee Rick Perry. Wright is also a fan of renewables, having personally invested in geothermal. However, Wright also thinks the threat of climate change is overblown. He has also stated that the DOE should focus on R&D and not commercialization. So from the world’s largest funder and researcher of next-gen energy, we will see less urgency on climate work, more focus on fossil fuel development, and may also see a pull-back in DOE loans and investments (the IRA alone committed $300 billion in loan programs to the DOE).

The Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 blueprint also describes breaking up the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), transferring some functions to other agencies, privatizing others, or placing them under state control. It describes NOAA as part of the “climate change alarm industry” and proposes eliminating much of its climate research, including marine carbon dioxide remove (mCDR).

In addition, everything the EPA and Department of the Interior do now will be gutted—or at least, the attempt will be made. Since the US requires comment periods, nothing will happen quickly. Also, changes that threaten public welfare and the environment will be immediately challenged in court.

Is the IRA at risk?

President Biden’s signature climate initiative, the Inflation Reduction Act, is the largest climate and green energy investment program in the history of the planet, responsible for 330,000 jobs and $370 billion in climate-related investments at all levels of government Many in Trump’s orbit (including energy companies, a number of Republican House and Senate members, plus House Speaker Mike Johnson) are going to push back on trying to kill IRA because of the massive job and investment loss that would happen in their states (Republican districts represent 85% of the new investments and 68% of the new job growth produced by the law). Repeal would only require a simply majority, though, since the law was passed under a budget resolution.

But if Trump tries anyway—if the IRA is going to be targeted because it came from Democrats (like Obamacare), or because it’s a ripe target for “efficiency” or for funding tax cuts—then what would “canceling” mean? Any action like this will likely be more symbolic than catastrophic since 90% of IRA-allocated funds have already been spent. However, what’s left will be vulnerable to getting repealed, rescinded, or impounded (where agency directors refuse to spend the money).

Brace for more climate disinformation

President-elect Trump, and most Republicans, have less trust in science than Democrats. And on average, there is less trust in science in the US than in the EU. Trump has made no secret of how he thinks climate change is a hoax, sea levels aren’t going to rise that much, and so on. What impact will this have on our ability to reach the public and policymakers with the truth? What impact will it have on our ability to convince the public that dramatic action is needed now to keep climate change from destroying our planet?

Other ripple effects

In a world where the US commits to climate action one year and cancels it the next, what kind of damper will this continued policy uncertainty have on future investments in climate at all levels (including the ability of multilateral agencies to raise the funds needed for climate work)? How about corporate attitudes toward and investment in sustainability programs? Will it matter if these aren’t incentivized, prioritized or rewarded by the federal government?

State-level impacts of a federal shift in focus will vary depending on funding and regulatory autonomy (be this permitting, coastal protection measures, etc.) Industry impacts will vary by type—DACCS, biochar, etc., because these different efforts are dispersed differently around the US and world.

Research will be impacted as well—the US could see a brain-drain to EU, Canada, and other countries who aren’t hostile to climate work.

Other ramifications might include four more years of judges who may be hostile to climate laws and regulations, a possible weaponization of disaster aid, and weakened protections for federal lands and forests.

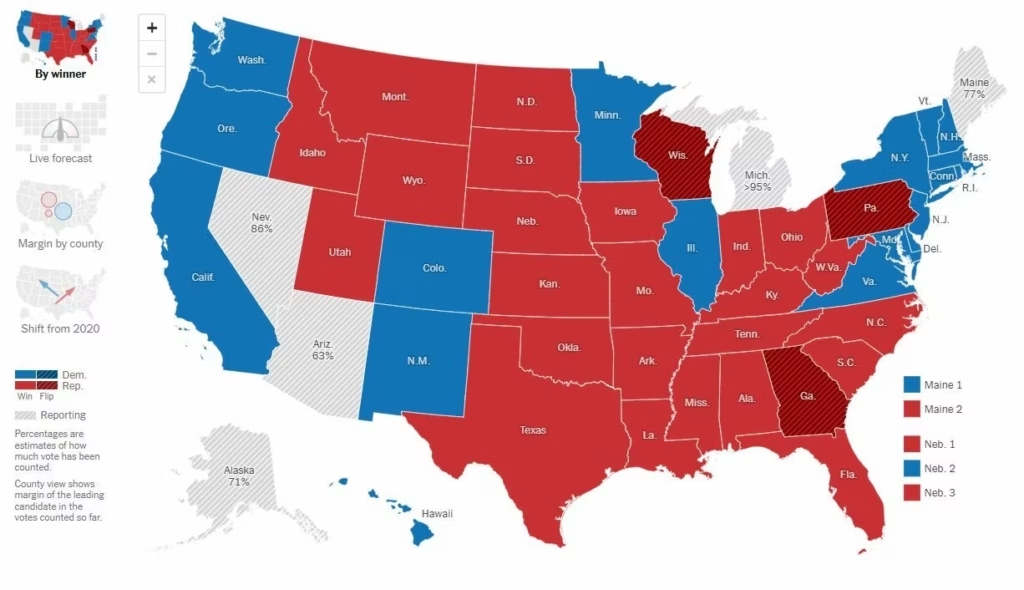

Image credit: Presidential Election Results Map: Trump Wins – The New York Times

The Global CDR Action Network (CDRANet) is a global, multi-stakeholder effort to help create global policy solutions for large scale atmospheric carbon dioxide removal. CDRANet is managed by the

The Global CDR Action Network (CDRANet) is a global, multi-stakeholder effort to help create global policy solutions for large scale atmospheric carbon dioxide removal. CDRANet is managed by the